Microeconomics is much older than the macro type. Yet, what is now taught really only dates back to the 1870s. ..It is entirely in the realm of theory and the mathematical treatment is rather odd. The following shows some of the strangeness of this fantasy realm. Note that when economists invoke micro reasoning in arguments, they are arguing by analogy — they are not describing reality (though too often an economist of orthodox convictions will confuse reality and fantasy).

– ‘Perfect Competition’ Evolves

It will always evolve from static absurdity

In Economics, the model of ‘perfect competition’, or pure competition as some prefer to call it, is a static construct that simply cannot remain static, if one is to take its set of assumptions seriously. ..Moreover, it would take a miracle for the initial conditions to all be met even in the fantasy realm of theory.

It should be noted that this model is considered by many orthodox economists as the ideal of market economics, a benchmark against which to measure all others. ..They do recognise that this ideal is unrealistic and unreachable. ..[In fact, it is absurd: ..rather like holding up a hairless dog with only three legs, and missing an ear, as the ideal canine.] ..Still, the orthodox are stuck with it, for they value what it facilitates.

Never mind that in this model each producer’s decision regarding how much to make hinges entirely on costs, ..specifically on the marginal cost of the next unit produced, ..which assumes that whatever gets produced gets sold at the market price, ..Believers in this model are expected to consider this is realistic.

Moreover, the set of assumptions that underlie the model also harbour a contradiction that changes the outcome considerably. Quite simply, following the assumptions will always lead to an evolution away from the starting scenario toward a very different outcome. ..And that starting scenario is so extremely unlikely, it is foolhardy to believe in it.

The usual presumption is that any producer in this model will have rising marginal costs. This is important mathematically.

Since the fixed cost per unit produced is falling as output increases, a rising MC means variable costs must be rising. But is it reasonable to presume this? Each producer is presumed to be at full capacity in output, so that additional output is hard to come by. ..So adding more workers means the additional ones cannot be as efficient in terms of extra product produced, and this gets worse as even more workers are added. Marginal cost (MC) per unit of additional output must therefore rise, so it seems. ..However, it entails there must be no spare production capacity in this sector.

But there are many such producers according to the set of assumptions, and they are all profit maximisers. ..Many of these owners, who are making good profits and naturally wanting more, will not be content to be static with a plant operating at full capacity. ..Indeed, what are the odds all of these independent producers would all be at maximal output at any one moment? ..Long odds does not begin to describe such a scenario. ..Unrealistic is the word.

Instead, some will expand their plant in order to produce more, sell more, have more income and more profits. What else could one expect a profit maximiser to do?

Spare capacity to produce

However, either after the initial such expansion or a subsequent one, such a producer will be unable to sell profitably all that can be produced by the expanded plant, and so will operate under the plant’s full capacity. ..Which means that particular producer’s variable costs will be flat for additional output at that point.

There will be several such producers, or more, facing the same situation, for the same reasoning will have motivated each of them to expand in order to get more profits. ..Their marginal costs do not rise steeply: ..indeed, they will not rise at all. On a graph, the line for MC will run parallel to and below the Average Total Cost line, as will the line for Variable Costs.

In short, instead of many producers at full capacity, as the assumptions of the model state, simply because these producers are profit maximisers, ..many will expand their plants, be unable to sell profitably all they could produce, ..and so run at less than full output with marginal costs that are not rising. ..Price is then no longer readily defined; ..this market is anything but perfect. ..And remember, all that gets produced is presumed sold at the prevailing market price.

Moreover, unless one is modelling some hypothetical realm where miracles are believed to occur with regularity, the initial starting conditions would never be met.

__Which is to say: a situation where all producing plants are at full capacity at the same time is so remote a likelihood as to constitute a miracle. ..Even granting such a miracle, its existence would be fleeting. ..In short, no perfectly competitive market can exist even in the fantasy world of orthodox economic theory.

It should be obvious that no actual market is ‘perfectly competitive’. ..Yet, the more extremist orthodox economists employ deliberately inflammatory language, labelling any actual market as suffering some degree of market failure because it is not ‘perfect’. ..According to this view… any actual capitalist market economy must be a failure due it being nothing but an agglomeration of ‘failed markets’. ..Fundamentalist extremism of this sort is truly absurd.

In conclusion, assuming owners strive for maximum profits cannot mean that producers are forbidden to expand their plants by making some fixed investment in them. ..And when they do so, their industry becomes one with spare productive capability featuring flat variable and marginal costs in the relevant output range. …This is the logical outcome of this ‘pure competitive model’ — it would always evolve into something quite different.

This website is.. regionalseats.ca/wp/

– Belief in ‘Economic Efficiency’

Can belief make it real?

True or False? ___ Economics is about how to efficiently use society’s limited resources to meet our many wants.

This assertion (or something very like it) is in all introductory textbooks, seemingly without exception. Though the notion may be quaint, it is a core aspect of orthodox doctrine. ..As such, it is a required belief.

Depending on how blinded by individualism the textbook writers are, the word ‘society’ may even be absent, despite the evident fact that we are organised in societies which are not mere collections of individuals.

Why even a vast herd of wild beasts is comprised of family groupings, and surely humankind is more organised than they. We are not just a swarm of locusts after all.

What economists mean by ‘limited’ is somewhat peculiar. Presuming that wants are unlimited, or at least indefinitely very large*, entails that anything less is by definition ‘limited’. …The implication then is that ‘resources’ also have limits. Which seems reasonable enough, though one of those resources in economics is something called ‘capital’. ..This is too big a topic to get into here, but its essence is money, or (more properly) credit. Typically, on a societal level, it is not the limiting resource.

Switching attention to ‘efficiently’, _ this concept is borrowed from engineering, where attaining the several objectives of a particular project, while employing the least resources overall to do so, is something to take pride in, a mark of the professional. On a project basis, economists certainly agree with this.

But of course economists also take the larger view of deploying the ‘limited’ resources of society to attain the largest output possible from them. Normally, however, the mix of output is never at all even close to the most optimal from a materials standpoint.

So while conceptually the efficient use of society’s resources sounds good, it is actually a rather surreal notion and certainly not anything to be expected in reality. Moreover, efficient use is really not the point. Effective use is a better way to view resource use, deployed towards some set of goals.

{ * note: Mandeville, writing much earlier than Adam Smith, made similar notice of how our wants might be thought ‘innumerable’. He was a somewhat scandalous figure who wrote a rather entertaining book in verses in praise of various vices. A relevant section is provided in an item on this website under “Veblen’s Latter Economics”.}

– Innovation Trumps Economic Efficiency

Well, of course, it does.

In respect of economic theorising, though fiddling with parameter values of an econometric model of an economy perhaps gives some sense of what may happen in the very near term, really the modeling of economists is devoid of a time dimension. Such models are static snapshots essentially.

Now, consider these snapshots of the world from 1800 to the present at half~century intervals: What do we see?

In 1800___ the Industrial Revolution had only nicely begun in England and America. Over a hundred textile mills in England were powered by steam engines, as were a few in New England. The metric system, ball bearings, and cigarettes were new, as was mass production using jigs to standardise parts. The railway excited inventors but was not yet a commercial reality. Under state sponsorship, former serfs in Denmark were obtaining freehold title to farmland. A manned hot air balloon had floated over France.

. By 1850___ railways were expanding rapidly. Steam engines were common, including in ships and riverboats. Cement, coal, and steel production were soaring; the metal industries were progressing. Some streets were arc~lit; some theatres had lime~lights. Many electrical devices existed, but as novelties. Large department stores, elevators, refrigeration, and sewing machines were all new. As were rotary printing presses, the dirigible, evaporated milk and carpet looms. Some horse~drawn farm machinery was available. Serfs in Russia were still oppressed; slavery still existed in the US. Chicago was about to boom.

By 1900___ modernity was rampant. Chemical industry had developed and plastics were known, though barely; rayon was novel. Petroleum was being refined for kerosene lamps, which meant whaling was about to cease. The telegraph and large circulation newspapers were keeping people informed. Telephones were novel, as was recorded music. Photography was well developed. the Eiffel Tower soared over Paris, while skyscrapers defined Chicago. The internal combustion engine was new and horseless carriages had appeared. Powered flight was near; dynamite made mining safer; and electricity had begun to light cities. Electric motors were about to change everything.

By 1950___ automobiles and trucks were widespread. Aircraft were common, though commercial jets had yet to fly. Container shipping was a concept. Coal was in decline while petroleum was soaring. Households were electrified and electric appliances common. Radio and recorded music were everywhere. Steam locomotives were being replaced by electrified lines and diesel locomotives. Tractors were replacing animal power on farms. A variety of plastics were in use; photocopying was being developed. Rockets and computers and television were novel. The transistor was about to change everything.

By 2000___ the world depended on satellite communication. Computers were ubiquitous and digital processes were rapidly displacing mechanical methods in many fields. Genetic manipulation was making an impact; nanotechnology was novel. Petroleum production had peaked in many countries. Container shipping had expanded world trade, The internet was changing communications. Newspapers were in decline; plastics were not. The Chinese economy had taken off but was not yet the behemoth it would soon become. The Americans were still bellicose, as had been the British in their imperial heyday, but the writing was on the wall and it was in Chinese characters.

New Technology

When the history of modernity is viewed in such widely~spaced snapshots, it becomes abundantly obvious that new technology fuels progress. ..So with what efficiency or inefficiency an economy utilises its resources at any given moment is truly a minor consideration. Yet that, rather than innovation, is the stated focus of economic studies. Students of the discipline are taught to focus on the wrong thing.

According to its textbooks, Economics currently claims to be about the efficient allocation or use of scarce resources on a societal scale. ..Yet instead, it should be about the introduction and use of new technologies and new techniques, about the institutional furniture conducive to same –about innovation.

Economic efficiency is a mirage ever receding into the future: for it is a static concept always in need of revision as economic circumstances change, as the balance of forces within an economy alters. Since it is in practice unobtainable, is economic efficiency even worthwhile having as a goal?

By far, the greatest gains in economic efficiency over time have come from the introduction of new technology and new techniques in production and distribution, from new ways of doing things. ..In the real world, as distinct from the hypothetical realm of theorising, gains in economic efficiency are a by~product of adopting such new ways, an incidental benefit of innovation. Foster innovation and leaps and bounds in economic efficiency will accompany it.

Scarce Resources

As for resources being scarce, where is the proof? In a world awash in consumer goods, scarcity seems an odd fixation. Of course, it is scarcity of productive resources rather than of products that economists presume, but still …. Are these scarce really?

Practically all materials have substitutes, in the sense that most things can be made with different materials, or made differently such that different materials get used. Meanwhile, scientists and technologists keep coming up with new ones, and they also develop ways of doing more with less material, so materials overall do not appear to be scarce.

Money never seems scarce in a productive economy. As for labour, there seems always to be some level of unemployment or under~employment. Moreover, many are employed in jobs that don’t need to exist, and only exist in order to create income for some employer.

So which productive resource is supposedly scarce? Is it energy such as liquid fuels and electricity? Seems like there are alot of options here, so not energy as such in some form. It is not running out. Some economists in the late 1800s worried that coal would be depleted in Britain. Now it is petroleum that may be depleted worldwide, aside from bitumen sands in Alberta and Venezuela. But energy in all its forms will not become depleted, not until our sun dies and that is not on anyone’s horizon.

Since Economics focusses on the wrong things, the advice of economists truly should be treated with much greater caution — huge caution, in fact. They are an ill~educated bunch, the economists: many seem more indoctrinated in the mysteries of the discipline instead of being well rounded in education.

The adoption of new techniques, new ways, new products is what drives our material existence forward. The conditions promoting same are what needs to be the focus of public policy by its makers. The overly confident suggestions of economists should be heavily discounted by policy makers. ..After all, they are frequently wrong.

– Marginal Costs Error

Correcting the usual diagram

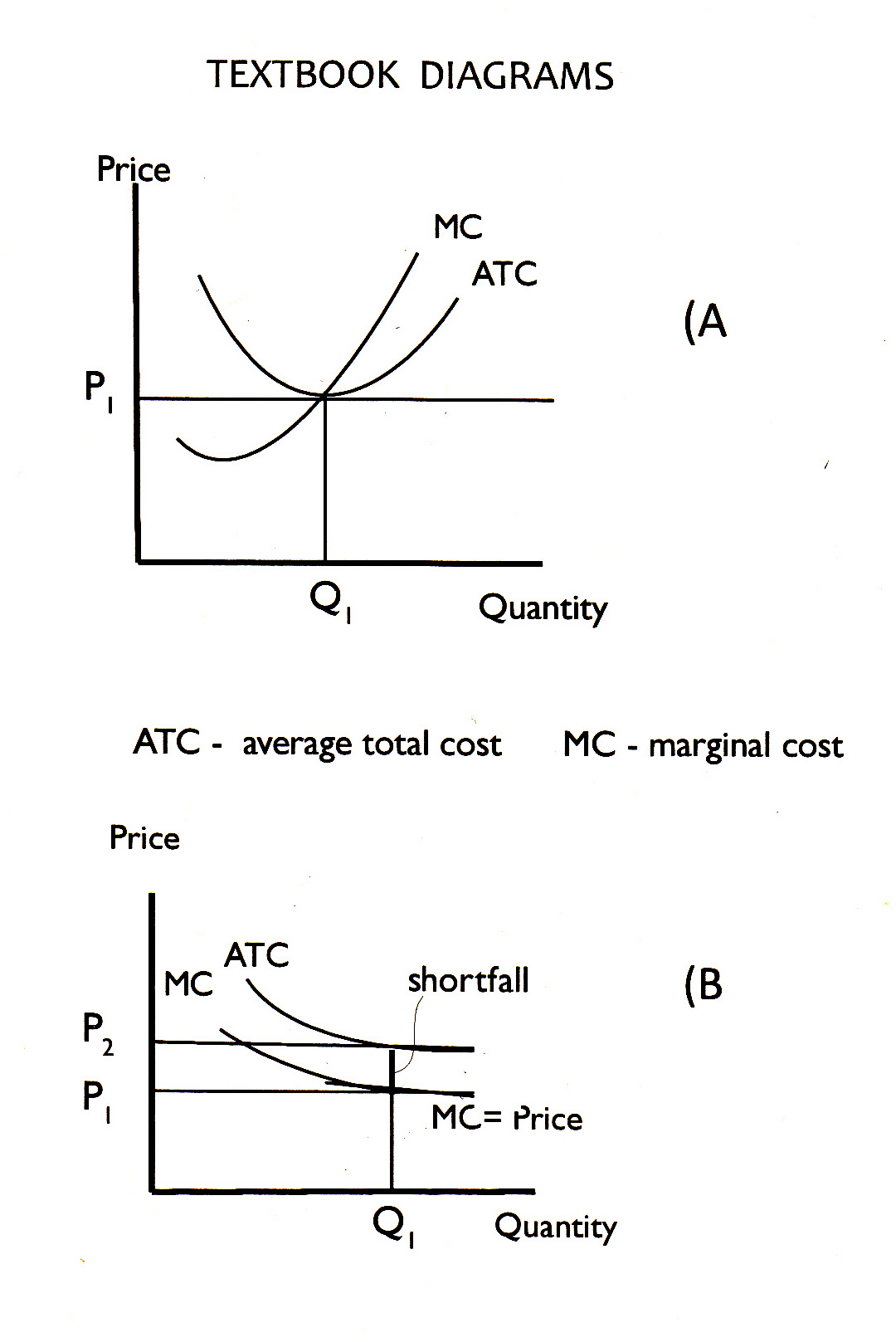

Below are two diagrams, A and B, which depict a marginal cost curve. Diagram A may be found in all textbooks of Economics that are used to teach Intro courses. It is a rather puzzling diagram for anyone familiar with production costing, since it shows the marginal cost (MC) of additional output as rising, which situation would be exceptional and likely impossible to find a realistic example of.

Why then depict something so very rare as being the normal case?

Moreover, if economists wish to consider their discipline to be scientific, then where are the field researches and surveys of manufacturers to show rising MC with volume of output? ..The impression exists that economists don’t want to know this presumption is contrary to fact. [They desperately need it as is.]

The other diagram shows the usual or typical situation experienced by producers. Notice that if price is set equal to marginal cost it would ruin the producer, because then revenues would fall short of total production costs.

In fact, setting price equal to MC is also known as “cut~throat pricing” because any producer so indulging is cutting their own throat. [This term was coined when straight razors were commonly used for shaving.] Producers who desire to stay in business do not lower prices to that level.

{By the way, there is another oddity about all this. Typically, production costs only are stated, as if marketing the product is without cost. At least, that is the impression one gets from such textbooks.}

Musings in an armchair

The armchair reasoning that led to diagram ‘A’ goes something like this: ..adding more variable expenses to a given quantity of fixed costs will inevitably arrive at a point of diminishing output for each additional bit of variable expenses, whereupon a stretch of rising marginal costs of output ensues. This rests on the presumption that each producer is operating at that plant’s full capacity such that additional output is not easily come by.

Such reasoning is faulty, however, as it ignores the mindset of the profit maximizing producer: ..For if that producer’s fixed plant is fully engaged and generating good profits, the natural inclination will be to expand the plant in order to produce more product and generate more profits. ..Really, what else would anyone expect an ambitious profit maximiser to do? …Sitting tight and being content is not their thing.

Inevitably, many will expand. ..though, naturally, at some level of output said expansionist producer will be unable to sell profitably all that may be produced in the first (or subsequent) expansion of plant, and then output will run under that expanded plant’s full output capacity.

Which is no bad thing from said producer’s position, for demand is naturally up and down for product, so having spare output capacity is very useful whenever business is brisk: ..Produce more; Sell more; Profit more. ..The ambitious profit maximiser of the assumptions of this model will act in his own best interest.

Having some extra output capacity, extra fixed plant, this producer’s marginal costs are of course essentially flat or declining for each additional bit of output. ..Many, if not most, producers seeking maximum profits will be thus situated. …The temptation then surely may be to compete for market share on the basis of variable costs alone, which is the so~called cut:throat competition.

Some with undue faith in the doctrine of the economists of orthodox bent might attempt this …because their doctrine claims price ought to be equal to a producer’s marginal cost. But it, like total variable cost at that output level, will fall short of total costs, as diagram ‘B’ depicts. ..Such price setting would be folly.

Where is the Proof?

The Economics textbooks which depict MC as rising also claim that Economics is scientific. Very well, then where is the proof MC is rising for most producers?

Not your armchair reasoning, but actual surveys of actual producers. ..And when those surveys show (as they will) that small producers selling into crowded markets(where they go with the market price, being price~takers) operate with spare capacity and have marginal costs which are flat or perhaps declining …Change what you teach your students. Quit force~feeding them false doctrine!

Either that or admit that Economics as currently taught is: …more religious than scientific; ..more a matter of blind faith than being based on evidence; ..more fantasy than reality.

Also, it is more a matter of indoctrination than education: …which is why it should never be taught to naive schoolchildren in secondary schools.

– The Mystery of Marginal Cost Pricing

Marginal Cost pricing is an article of faith for Believers of orthodox theory in Economics, and though MC pricing does not withstand logical analysis, the orthodox cling to it anyway. ..Which makes their belief in it quasi~religious in nature.

In order for Price to be equal to a producer’s marginal cost, either that producer has discretion to set Price and will choose to do so equal to his marginal cost for the amount being produced, ..or said producer is a price taker and chooses to keep producing until the marginal cost of the next unit made is the same as that price. ..In theory anyway, supposedly this is how it all works. Let us examine this.

Four general types of markets are recognised by orthodox economists — these being: ..Monopoly; ..Oligopoly; ..Differential competition; and Pure competition. Price for all of them is typically an abstract quantity.

Of course this is not true in practice. Monopolists certainly offer their output at different prices to different market segments, and oligopolists will do likewise when they can. Seasonal variation in pricing is common for many products, and pricing for some services if often different by time of day.

However, all this is too much clutter for easy analysis, which using abstract Price avoids — so be it, let Price prevail. ..Except for Oligopoly analysis, where abstract Price is so difficult for economists to handle, they typically revert to narrative instead, with game theory usually being deployed.

>> Monopoly and Oligopoly analysis have a more pressing problem. Marginal costing for both of them is typically wrongly perceived. Both usually have spare productive capacity and are thus able to produce additional output well below whatever prices it will be sold at.

In which case MC and Price simply never meet. If either monopolists or oligopolists used MC=Price as their guide in setting prices, they would be losing money.

>> Differential competitors have some unique aspects to their product or service, but also face competitors offering products perceived by buyers as close substitutes. So differential competitors will want spare capacity to produce in order to meet whatever extra demand might come. If they can’t, potential customers will go elsewhere.

Having some spare capacity to produce, the differential producer has a marginal cost below the price being charged. ..Here also marginal cost pricing would entail operating at a loss.

>> Pure competition, also known as a perfectly competitive market, is acknowledged not to exist in reality. ..Its existence is confined solely to the fantasy realm of pure theory. ..What is not usually acknowledged is the necessity for a miracle to allow it to exist even there. For the assumptions of that model require all its numerous producers to be at full plant capacity, such that additional output comes at increasing costs per unit for any of them.

But a situation where all producing plants are at full capacity at the same time is so remote a likelihood as to constitute a miracle. Even granting such a miracle, its existence would be fleeting. ..In short, no perfectly competitive market can exist even in the fantasy world of orthodox economic theory.

Conclusion — Marginal Cost Pricing does not exist for any of the market types recognised by orthodox Economics. ..It should be on the discard heap of dead theories. ..That it is not simply shows that Economics is no science.

– Utility & Income

Leveling of Incomes

Goods and Services get bought, and it is presumed they must be of use to the purchaser. Another way of expressing this is to claim they are of utility to the purchaser, which is the same thing. Or of benefit to the purchaser. Benefit and utility in Economics are empty categories: that is, they have no real content.

Sometimes the act of purchasing is of more utility than the item or service acquired. Women speak of ‘retail therapy’, meaning going shopping makes them feel good about themselves. The attention of shop assistants is gratifying. Shopping itself affirms their status as a consumer, and if they spend enough, as an up-scale consumer. It boosts their self esteem and may reinforce their status with their peers in the social order. What is bought is often enough of secondary importance. Sometimes what is bought goes straight into the closet, never to re-emerge. Still, if shopping in itself makes one feel good, that also is a benefit to the shopper, however little related it may be to what is actually acquired.

Economic analysis is about goods and services sold at what prices: quantity and price is all. ..Utility and any imputed benefit are redundant to the analysis. Their purpose is essentially political: to make the prices paid seem fair, the claim being this satisfies the buyers’ needs, hence they are willing to pay those prices. Thus is value determined, by price willingly paid, or willingly received when selling one’s labour. Reluctantly paid makes no difference – paid is paid.

This contrasts with the earlier notion that value arises from the amount of labour involved in production of the good or service. [It is worth noting that Lauderdale dismissed this as early as 1804, saying price is set by what a buyer willingly pays.] _ Marx manipulated the labour theory to claim workers were paid less than their value to production. _Wages received today are said to be the benefit for leisure foregone by a worker: That is the bargain struck, according to orthodox believers. Leisure forgone?

Yet, the degree of buyer satisfaction is individual and depends on one’s purse, which leads to the awkward issue of income transfer. It is usually presumed that benefit may be stated in money. However true that may be, the translation differs by income class. Stands to reason that anyone with low income will value 500 dollars moreso than a high income recipient. It simply means more to a person with $15,000 annual income than to a person getting $200,000 a year. Hard to imagine anyone arguing otherwise in seriousness: unless that person is rather twisted.

To the extent that orthodox doctrine makes use of utility or benefit as a measure of value, and argues that an ‘efficient’ deployment of ‘limited’ societal resources maximises such utility within society, then implicitly the doctrine endorses maximal utility as a worthwhile goal. And since some additional dollars to someone in the lowest — or near it — income class has more benefit than that same amount for a high income recipient, then this must be true: That the disutility of transferring some money from that higher income class to a lowly one is more than offset by the gain in benefit by that lowly class, and so societal utility collectively is greater than if no transfer occurs.

Conclusion: ..An orthodox economist must either endorse the sort of income levelling the Scandinavian countries have in some degree, in pursuit of maximising utility within a society, and therefore be a socialist or condone such a socialist measure; ..or else in opposing same become a hypocrite, for socialism is where orthodox utility doctrine ends up. Which on the whole turns out to be a Good Thing, as economies with less of an income spread generally perform better due to stronger consumer spending.

– Supply and Demand in Classroom Economics

The importance of graphs.

In the classroom, supply and demand explanations hold a prominent place in introductory courses in Economics. In order to make things seem realistic, real life examples are often employed, with the interpretation of events running along the lines of “this must have happened.”

Graphs are used that depict demand and supply as criss/crossed lines (which may be curved) whose intersection is said to be what quantity can be sold at that price. Explanations involve movement along either line, often also with a shift of one or both curves parallel to the first ones. Most situations involving quantities sold at what prices may be interpreted using such graphical analysis, though the explanations might not be very realistic.

Use of these graphs dates back to 1890 when Alfred Marshall in England published his Principles of Economics. It became a standard textbook on both sides of the Atlantic for some decades, going through several editions. Said graphs usually presume the existence of many buyers and multiple sellers of that product or service, though this might not be explicitly stated. Typically also, the real life examples used are not of this nature.

Outside the classroom

Coincidental with Marshall’s textbook appearing and gaining acceptance, finance capitalists were taking control of large segments of many advanced economies, consolidating industries that thereafter competed mainly in marketing and much less often in pricing. Market supply is heavily influenced by the decisions taken by the price leaders in the various consolidated industries, who set the prices that others tend usually to follow.

In order to maximise their total profits for each product, large companies then tailor their output to what they expect can be sold at prevailing prices. They have little interest and no incentive to produce more if it can only be sold at a lower price that results in less profits in total for them. Indeed, if sales are sluggish, a company will usually reduce production so as to clear any excess inventory at prevailing prices.

However, among competing product offerings from several companies, some will be more popular with customers than are others. This is often due to the features each has or the styling, or perhaps due to better promotion. A company with less desired offerings may need to lower its prices in order to move product. This is not price competition so much as an admission of failure in product offerings. It lowers the company’s profitability, which generally then affects the company’s stock price, something that can have adverse consequences for its top management. Lowering prices is not something embarked upon with any enthusiasm.

Influencing sales

Companies use advertising and other types of promotion to increase sales, in an effort to grab market share from competitors. Such competitive promotion may also increase sales of their industry sector relative to others. For example, promotion of specific tourist destinations might boost tourism in general. The state of the overall economy also greatly influences sales, particularly of large ticket items such as home renovations, transport vehicle sales, or destination vacations.

Yet, such large influences on buying by consumers is what gets interpreted by the supply/demand criss/cross graphs. But as already stated, these typically presume a competitive marketplace of many buyers and multiple suppliers. Orthodox explanations tend to involve price competition, new entrants, those sorts of things. So, be aware that that supply and demand analysis is often a mishmash of wishful thinking and interpretation of real data — something more speculative than reliable, particularly regarding supply.

More about supply …

The usual criss/cross graph depicts a market of many buyers and multiple suppliers. The supply curve slopes upward, indicating that as price increases so does the amount available for purchase, while at lower prices less will be offered by suppliers. But in reality suppliers typically are few, and they are generally unwilling to lower prices, so the graph’s supply curve is inaccurate. It should be a flat horizontal line below a certain expected (wanted) price, rising only at prices above that. Suppliers tend to reduce production without cutting prices.

Or more correctly, the marketer will not cut prices, supply being a marketing decision that may have little to do with cost of product. This reflects the limited number of major suppliers for most products or services. Nowadays, the companies who are the major marketers of any particular product often outsource production, often to countries with lower wage rates. ___ Ain’t ‘free trade’ marvelous?

Marketing is about making something sufficiently scarce, or seemingly special, that consumers willingly pay more for it. Companies anticipate a certain sales level at the chosen price, and if sales exceed expectation, so much the better. But should they be sluggish, price may be set higher in order to make more per unit and thereby reach the total profits expected. This is contrary to the orthodox dogma of the criss/cross graph, the so-called ‘scissors of supply and demand’.

Instead it is more a market of oligopolists. However, this does not occupy the centre of classroom explanations about markets, certainly not in introductory courses.

note:__ an exception can be the retailing of groceries, where low prices and high turnover may be the formula for adequate profits, at least for many items. Then again, maybe I am being too kind to grocers, for on some items their margins are clearly rather high.